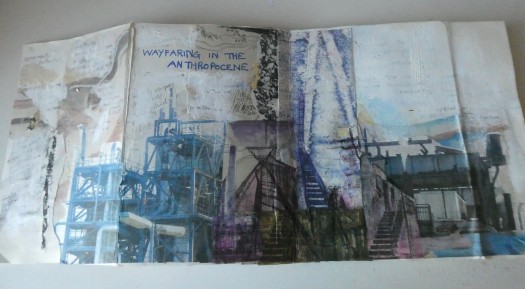

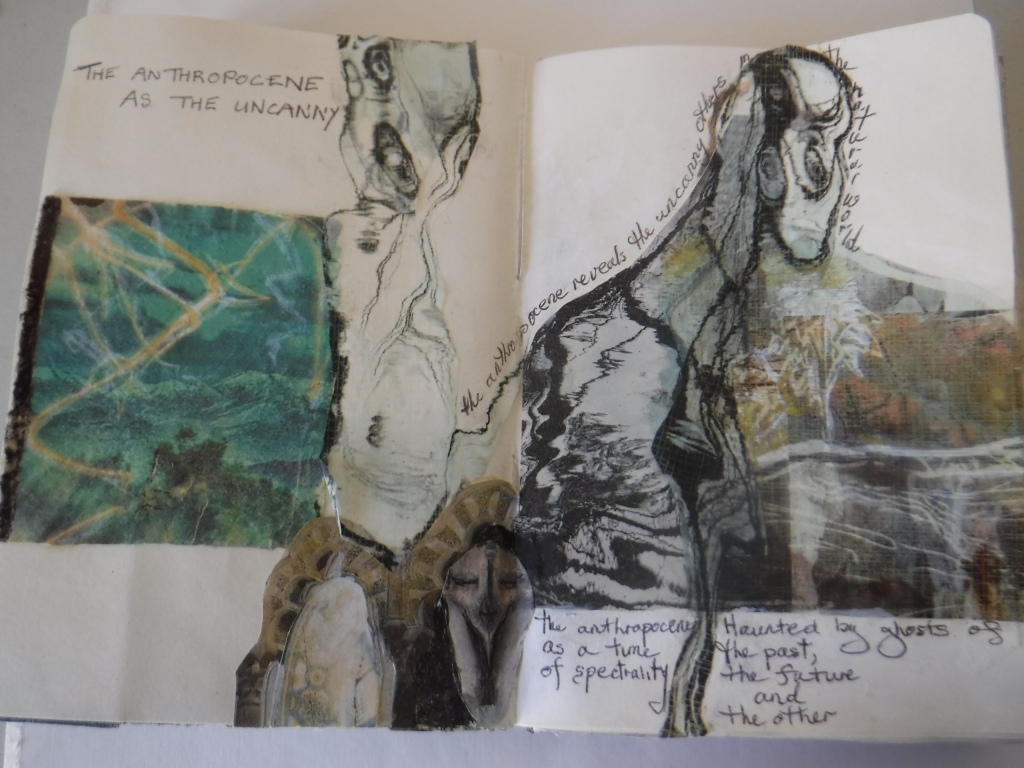

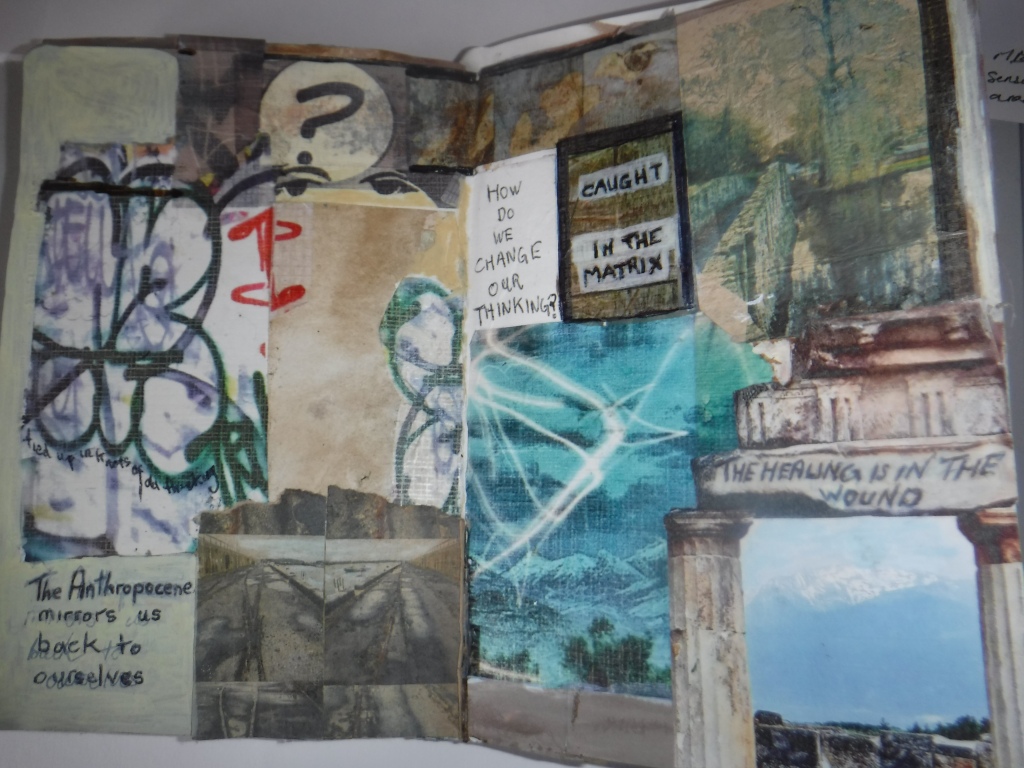

So far in this series of articles I have been focusing my attention on the psychological impact of living in the Anthropocene and on philosophical responses to this. Now I find I have to confront head on the fact that it is extractive capitalism that has bought us to this environmental crisis.

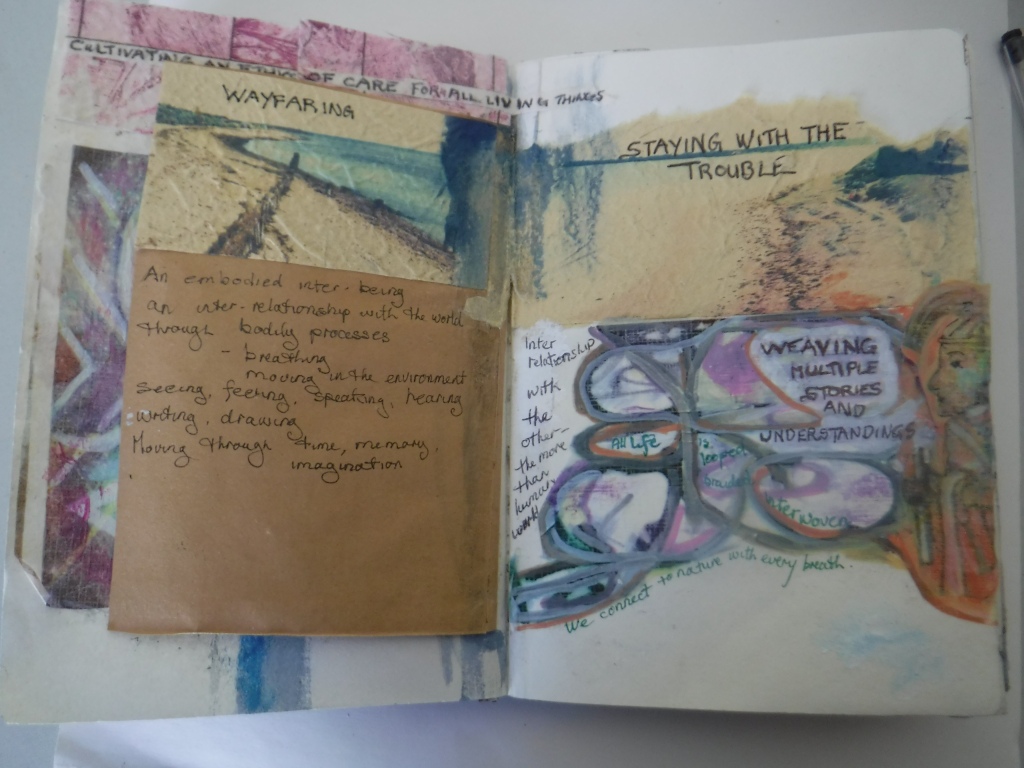

All of the posts in my series on the Anthropocene are exploratory. I am not setting myself up as an expert. What I am doing is searching the internet for information that seems relevant then compiling it into these posts.

Since the end of WW11 the accelerated activities of extractive capitalism have created the ecological, cultural and social challenges that now confront us. The endless need of capitalism to continue growing has led to a globalized economy based around ever increasing industrial production and technological developments.

Alongside this a consumerist lifestyle has been actively promoted. While those who can afford to buy the goods and services on offer live very comfortably, the people at the margins are experiencing economic hardship and social injustice.

Globally, the top 10% of emitters were responsible for almost half of global energy-related CO2 emissions in 2021, compared with a mere 0.2% for the bottom 10%. The top 10% averaged 22 tonnes of CO2 per capita in 2021, over 200 times more than the average for the bottom 10%… The richest 0.1% of the world’s population emitted 10 times more than all the rest of the richest 10% combined, exceeding a total footprint of 200 tonnes of CO2 per capita annually.

https://www.iea.org/commentaries/the-world-s-top-1-of-emitters-produce-over-1000-times-more-co2-than-the-bottom-1

Since the 1980s and the era of Margaret Thatcher and Ronald Reagan, neoliberal policies have promoted privatization, deregulation, tax cuts and free trade deals that have favoured huge industrial corporations. These corporations are increasingly controlling the fate of Earth and our collective destiny.

A study published back in 2017 is one of the most up-to-date reports on all companies around the world and their carbon footprint. It reveals that just 100 of all companies have been responsible for 71% of the global greenhouse gas emissions since 1998.

Additionally, if companies continue to extract fossil fuels at the rate they have been doing over the past 28 years, it is estimated that the global average temperature will rise by up to 4°C.

https://peri.umass.edu/greenhouse-100-polluters-index-current

Of these companies, global coal and oil corporations head the list.

The counter argument to these statistics is that most of us consume fossil fuels. We are told we must change our light globes, recycle plastic containers and buy organic vegetables to reduce our carbon footprint. While all of these measures play a part in curbing greenhouse gases and environmental pollutants it is not until global companies take responsibility for their actions that carbon emissions and environmental degradation will be reduced.

Neo-liberal policies have ensured holding these companies to account is extremely difficult. Government policies in the Western world generally favour corporations over the general public. Here in Australia, we are constantly told that the mining industry forms the backbone of our economy and that implementing green policies will take time and is likely to result in job losses and uncomfortable disruptions to our way of life. Fossil fuel industries promote their activities by telling us they are aiming to be ‘carbon neutral’ but never explaining exactly how they plan to do this. This kind of greenwashing appears to be happening across the industrialized world.

At the same time we are constantly encouraged to consume more while being led to believe that those who are experiencing poverty and homelessness have somehow bought it in on themselves by making poor choices. Across much of society there is an attitude that those who are struggling are somehow personally responsible. As a result, economic hardship has become a source of guilt and shame for many experiencing it.

All this is compounded by the rise of authoritarian neoliberal politics across the globe. In an article on the subject Ian Bruff and Cemal Tansel state that:-

“contemporary capitalism is governed in a way which tends to reinforce and rely upon practices that seek to marginalize, discipline and control dissenting social groups and oppositional politics rather than strive for their explicit consent or co-optation.” https://eprints.ncl.ac.uk/file_store/production/278697/C115B613-E3A4-4B04-BCAC-603F24A25314.pdf

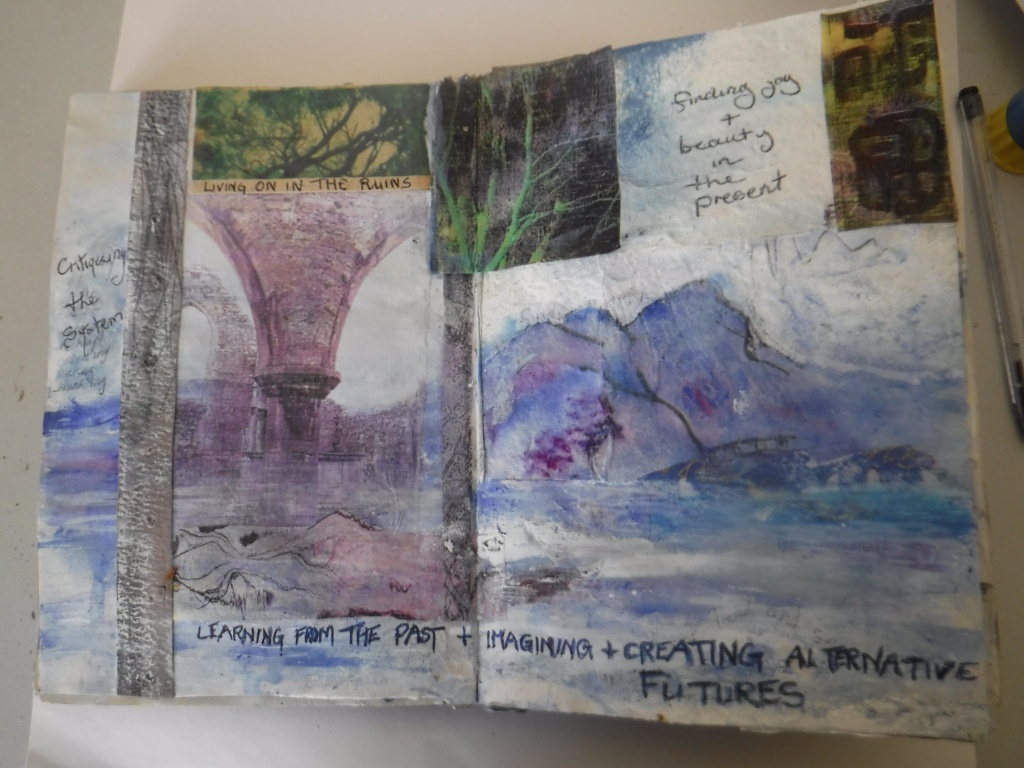

As the ecological crises deepen we are faced with difficult truths about how our world is governed and how this governance is exacerbating the issues that confront us.

…to be continued